Picture this: It’s 100 AD in Rome. Marcus, a legionary soldier, just got his quarterly pay—75 freshly minted silver denarii jingling in his leather pouch. Meanwhile, in 2025 Germany, Sarah, a mechanical engineer, checks her bank account: €2,850 deposited after taxes. Who’s richer?

The answer isn’t what you’d expect. When we measure wealth in gold and silver—the ancient standard—modern engineers are crushing it, earning 60 times more in precious metals. But when we look at what really matters—what you can actually buy with your paycheck—the story gets a lot more interesting.

Let me take you on a journey through time, comparing cold hard denarii to warm digital euros, to answer a question that’s been bugging me: are we better off than our ancestors

The Roman Soldier’s Wallet: Not as Fat as You’d Think

Let’s start with Marcus, our Roman legionary. In the early 2nd century AD (under Emperor Domitian), a regular soldier earned 300 denarii per year. Sounds decent, right? Hold that thought.

The Roman army had a nasty habit of “helping” soldiers manage their money. Before Marcus saw a single coin, the military accountants deducted about 50% for food, equipment, clothing, and even hay for the squad’s mule. His boots wore out constantly on those long marches, and every replacement came out of his pocket.

After all these deductions, Marcus took home roughly 150 denarii per year, or about 12.5 denarii per month. That’s his actual spending money.

Now for the prices. Here’s what things cost in ancient Rome:

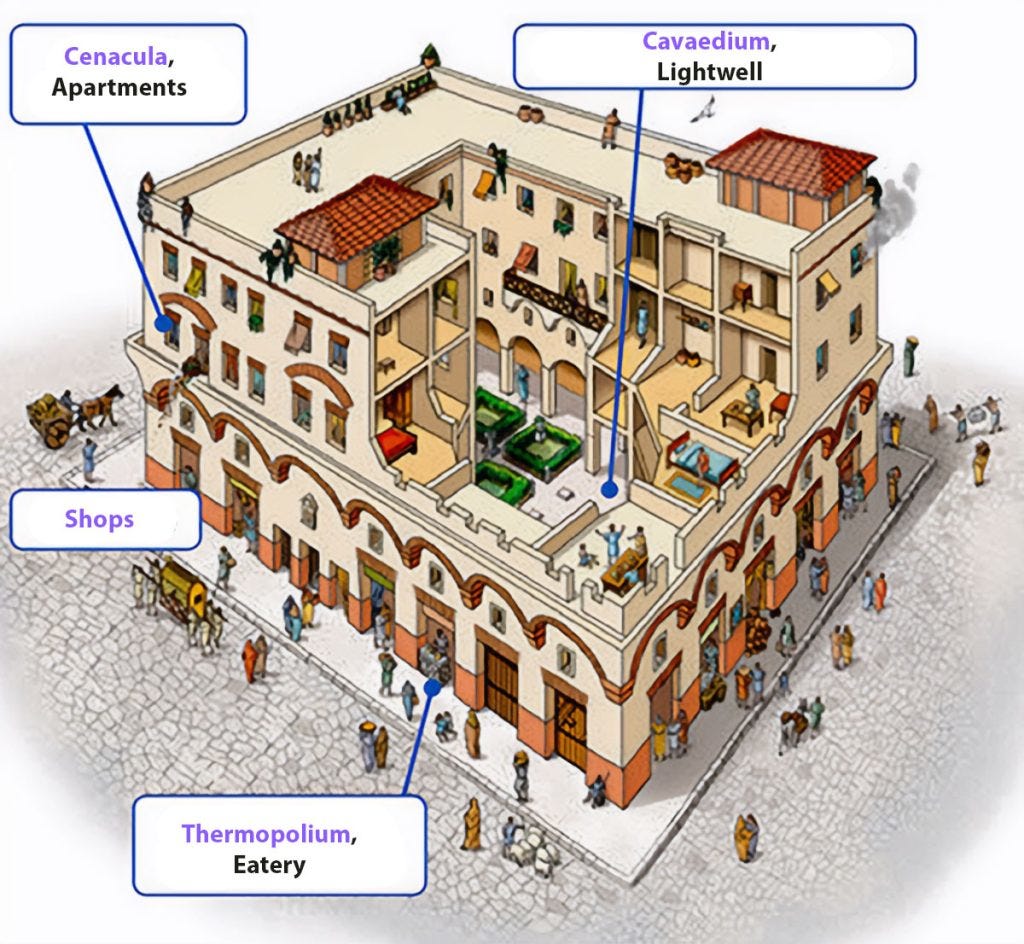

A horse: 125 denarii (his primary “used car” option)

Cheap apartment rent (outer Rome): 30 denarii/year (2.5/month)

Daily bread: About 1 as (1/16 denarii)

A modius of wheat (enough for ~20 loaves): 1 denarius

Public bath entry: 1 quadrans (1/64 denarius—basically free)

Cheap wine (per pint): 1 as (1/16 denarius)

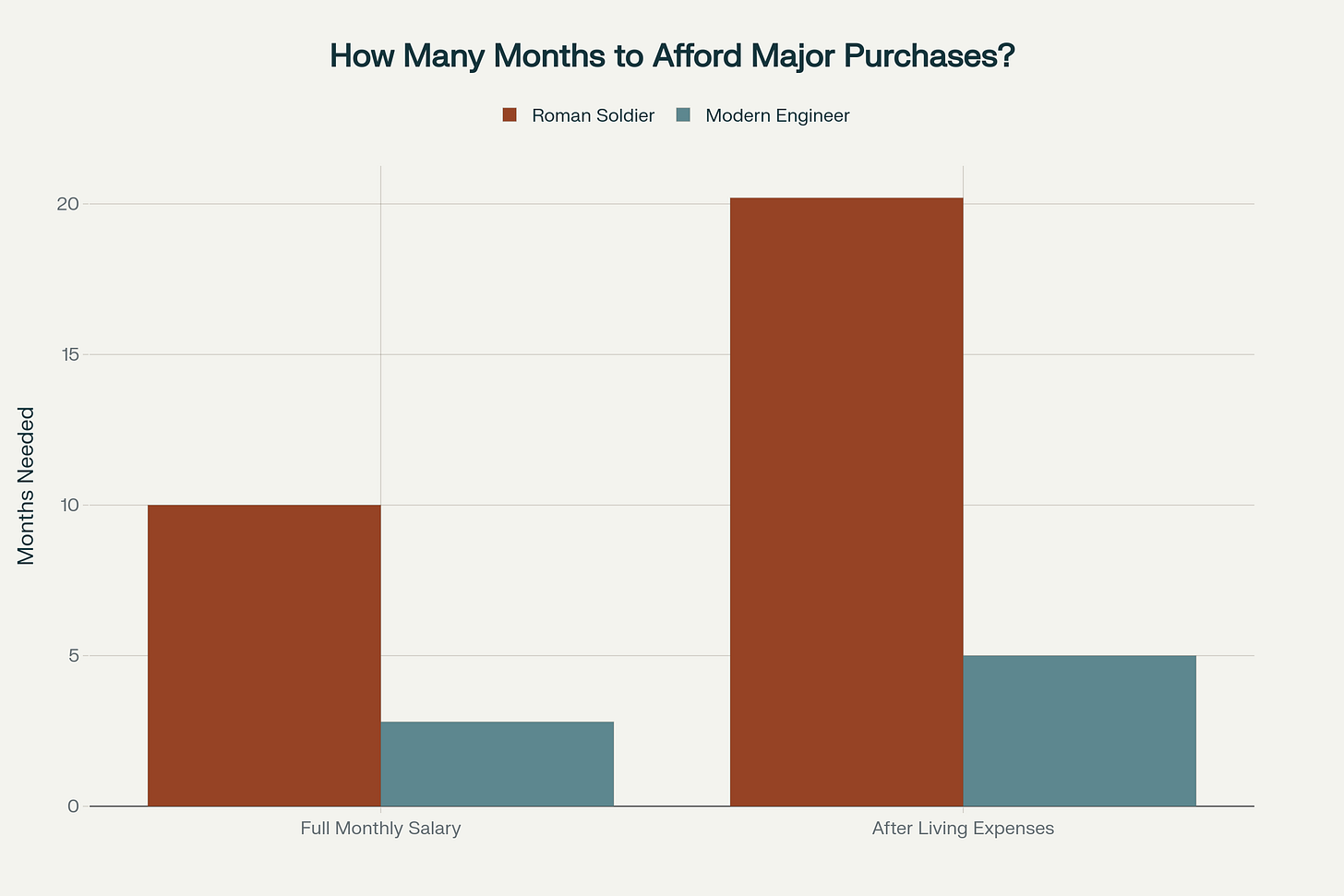

The big shocker? A horse cost 125 denarii—nearly Marcus’s entire annual salary. Even after paying rent and food, it would take him 20 months of saving to afford his own horse.

The Roman Soldier’s Wallet: Not as Fat as You’d Think

Let’s start with Marcus, our Roman legionary. In the early 2nd century AD (under Emperor Domitian), a regular soldier earned 300 denarii per year. Sounds decent, right? Hold that thought.

The Roman army had a nasty habit of “helping” soldiers manage their money. Before Marcus saw a single coin, the military accountants deducted about 50% for food, equipment, clothing, and even hay for the squad’s mule. His boots wore out constantly on those long marches, and every replacement came out of his pocket.

After all these deductions, Marcus took home roughly 150 denarii per year, or about 12.5 denarii per month. That’s his actual spending money.

Now for the prices. Here’s what things cost in ancient Rome:

A horse: 125 denarii (his primary “used car” option)

Cheap apartment rent (outer Rome): 30 denarii/year (2.5/month)

Daily bread: About 1 as (1/16 denarii)

A modius of wheat (enough for ~20 loaves): 1 denarius

Public bath entry: 1 quadrans (1/64 denarius—basically free)

Cheap wine (per pint): 1 as (1/16 denarius)

The big shocker? A horse cost 125 denarii—nearly Marcus’s entire annual salary. Even after paying rent and food, it would take him 20 months of saving to afford his own horse.

The Modern Engineer’s Reality Check

Fast forward to 2025. Sarah, our mechanical engineer in Germany, earns about €40,000 gross per year—pretty average for her profession. After German taxes and social insurance, she nets €2,850 per month, or €34,200 annually.

Her costs look like this:

Used car: €8,000

1-bedroom apartment (outside major cities): €950/month

Groceries: €300/month

Gym membership: €30/month (the modern bath house)

Bread: €2.50/loaf

To buy that used car, Sarah needs to save for 5 months after her living expenses, or 2.8 months if she used her entire salary. That’s 4 times faster than Marcus could save for his horse.

The Numbers Don’t Lie—But They’re Complicated

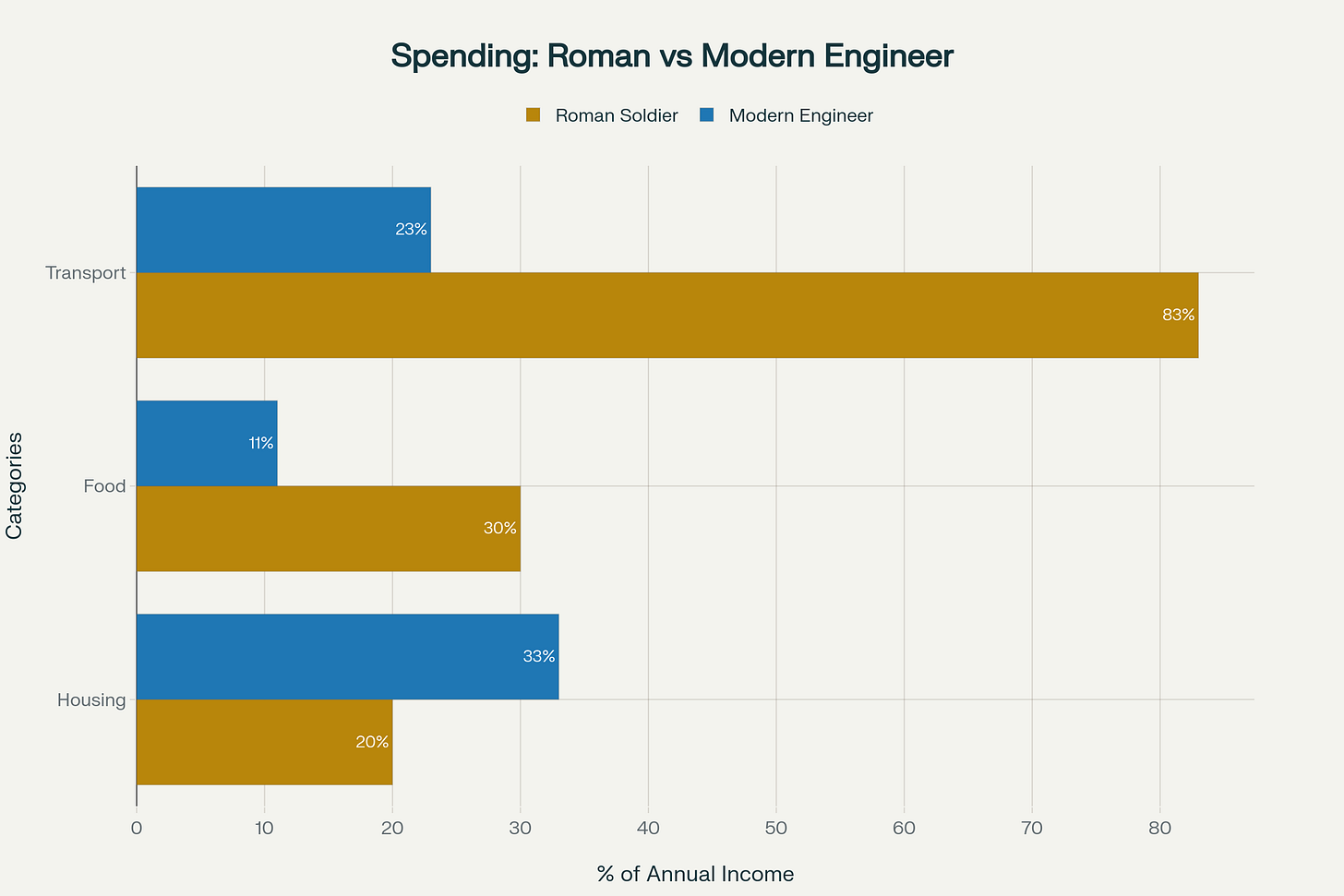

Here’s where things get really interesting. When we compare the actual percentage of income spent on life’s necessities, we see something surprising:

Housing: Marcus spent 20% of his income on a cheap apartment; Sarah spends 33%[calculation]. Winner: Roman soldier.

Food: Marcus spent 30% on basic food; Sarah spends 11%. Winner: Modern engineer by a mile.

Transport: Marcus would need to spend 83% of his annual income for a horse; Sarah needs 23% for a used car. Winner: Modern engineer, massively.

But wait—let’s talk about the elephant in the room: silver and gold. Each denarius contained about 3.9 grams of silver under Augustus. That means Marcus earned 585 grams of silver per year, worth about $600 in today’s silver prices.

Sarah’s €34,200 salary equals roughly $37,600—or 36,566 grams of silver at current prices. She earns 62.5 times more silver than Marcus.

So did the engineer get poorer? In precious metals terms, absolutely not. She’s crushing it. But there’s a twist: silver used to be far more valuable relative to other goods. In Roman times, the gold-to-silver ratio was about 12:1. Today it’s around 119:1. Silver’s value collapsed relative to everything else.

The Big Picture: Who Lived Better?

Let’s be honest about what we’re comparing. Marcus faced:

25 years of mandatory military service

High risk of death in combat or from disease

No vacation days

50% chance of dying before retirement

Basic diet with limited variety

Potential for extreme wealth at retirement (3,000 denarii bonus = 20 years of pay!) if he survived

Sarah faces:

40-hour work weeks with 25-30 vacation days per year

Low job-related health risks

Modern medicine ensuring ~80-year life expectancy

Diverse, abundant food supply

Stable retirement pension

Access to all modern technology and knowledge

In terms of raw purchasing power measured in gold and silver, the modern engineer is phenomenally wealthier—about 60 times richer in precious metals[calculation]. But silver and gold are less important today because we’ve created so much more economic value through technology.

In terms of quality of life, it’s not even close. Sarah has access to technology, medicine, food, entertainment, and safety that ancient Romans couldn’t even dream about. She lives twice as long, works half as hard (in terms of physical danger), and has options Marcus never had.

But here’s the surprising part: in terms of relative economic position within their societies, they’re closer than you’d think. Both are middle-class workers in their respective economies. Both spend roughly half their income on housing and food. Both need to save several months’ wages for major purchases. Both have job security and a path to retirement (if Marcus survives).

The Verdict: Did Engineers Get Poorer?

Measured in gold: Hell no. Modern engineers earn 60x more precious metal.

Measured in lifestyle and life expectancy: Still no. Modern life is incomparably better.

Measured in relative economic stress: Maybe slightly. Housing takes a bigger bite of Sarah’s income (33% vs. 20%), but she spends far less on food and transport.

The real story isn’t about whether we got richer or poorer—it’s about how completely our economy has transformed. Silver used to be money itself; now it’s an industrial commodity. Horses used to be the height of transport technology; now we have cars that cost less (relatively) and perform better.

We don’t just earn more than Roman soldiers—we live in a fundamentally wealthier world where food is abundant, medicine works, and you can visit the world’s knowledge from a device in your pocket.

But if you ever feel underpaid, remember: at least you don’t have to spend 10 months’ salary to buy a horse that might kick you in the head.

All monetary calculations based on historical sources from Roman military records, archaeological price data, and modern salary surveys from 2025.